Key Findings

- Indonesia’s plasma scheme was designed to cut villagers in on the profits from the palm oil boom. But a decade after giving up their land, some are earning less than a dollar a day and still paying off vast debts.

- As plantations rapidly expanded, communities were tied into opaque, decades-long contracts that gave companies expansive control over their land and finances.

- Some of these contracts may be illegal, according to a leading government watchdog, which has investigated at least 20 cases.

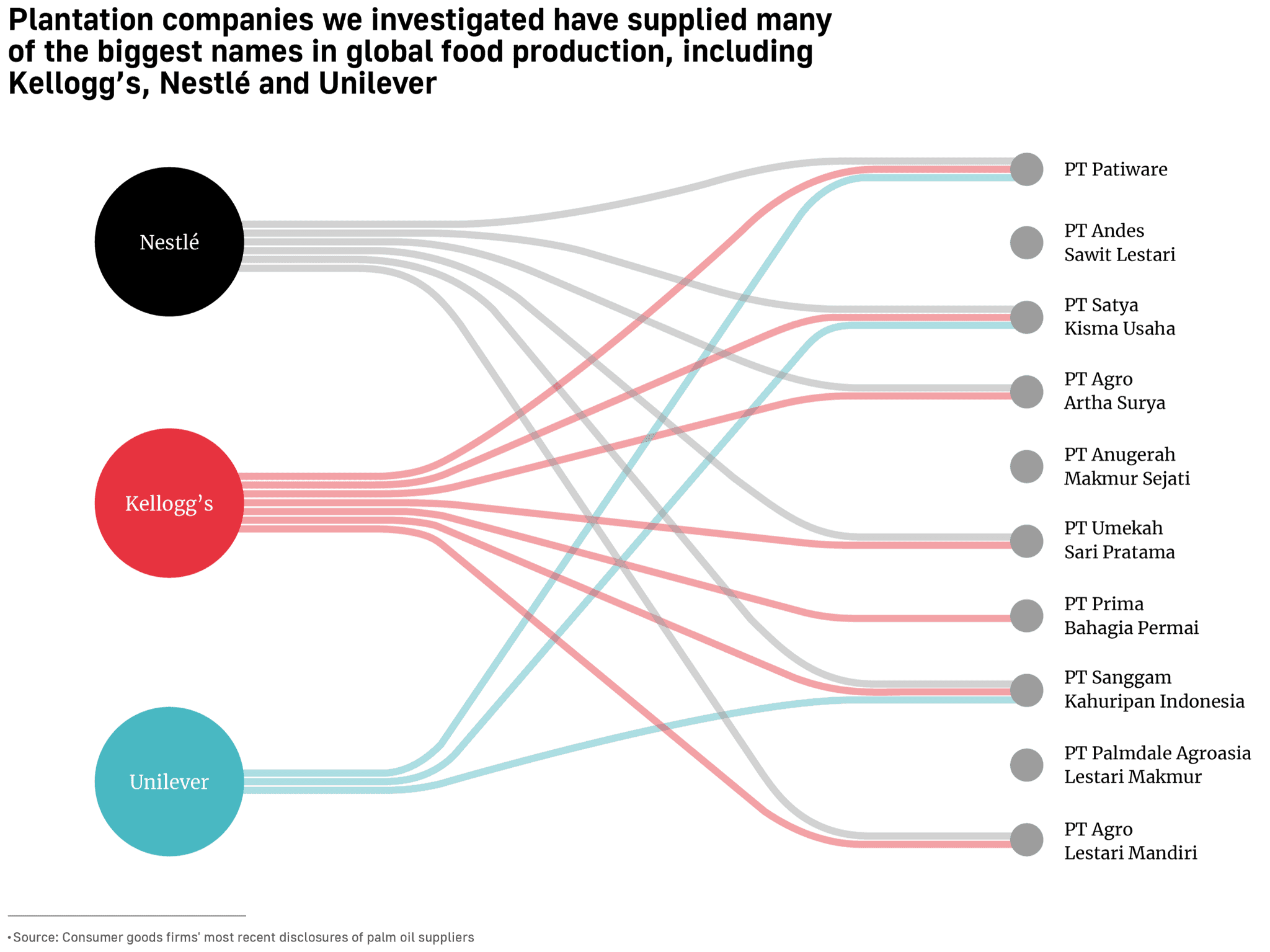

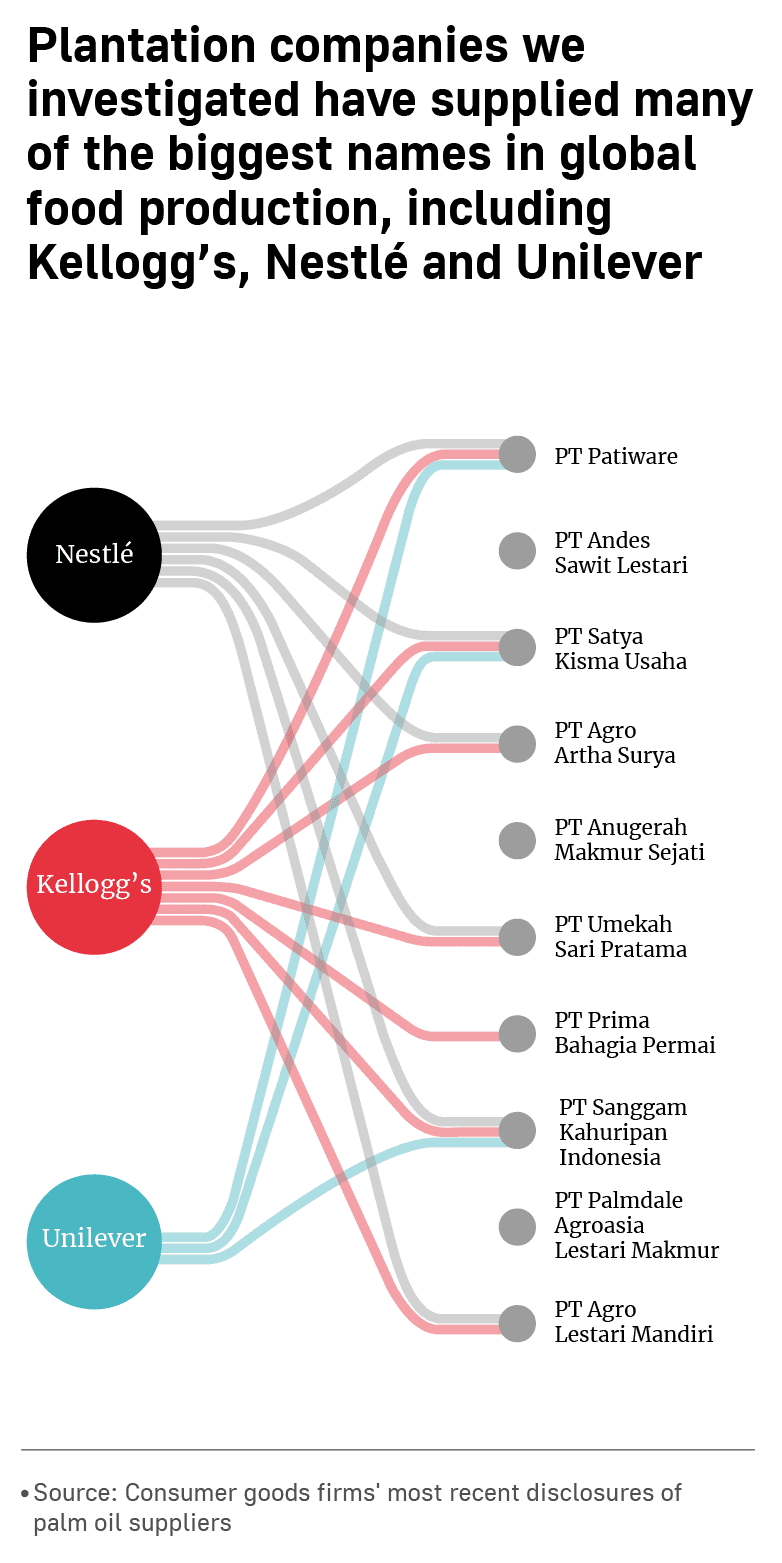

- Palm oil from plantations where communities are trapped in exploitative schemes is flowing into the supply chains of firms like Nestlé, Unilever and Kellogg’s.

This article is the product of a collaborative investigation between The Gecko Project, Mongabay and BBC News. Read a PDF version (5MB) here

Sit back, do nothing and watch the money roll in.

That was the promise made to villagers across Indonesia as they were asked to give up control of their land to corporations in exchange for a share in the profits from oil palm plantations.

But for some communities, it was little more than a mirage. More than a decade later they are earning less than a dollar a day — and find themselves submerged in millions of dollars of debt.

“We don't eat bones any more, we eat water,” said Rifai, a villager from the island of Sumatra. “Everything goes to the company.”

Since the 1970s, palm oil has offered communities in Indonesia a route out of poverty. As global demand grew for the commodity — to produce a dizzying array of products, from soap to chocolate to biofuels — plantations sprung up across the country. The nation became the world’s largest producer, sending millions of tonnes each year to Europe and the US and generating billions of dollars in profits.

The Indonesian government sought to ensure villagers would benefit by encouraging companies to give them a slice of their plantations. In the early years, they were handed a physical plot of land to tend - known as “plasma”. They harvested fruit and sold it to corporate-run mills, the first step in a supply chain that stretched from tropical islands to supermarket shelves.

In the mid-2000s, as the industry experienced its most rapid phase of growth, it became a legal requirement for privately-owned firms to provide a fifth of their plantations as plasma. But at the same time a new model became dominant. Instead of providing communities with their own plots, the corporations would manage the entire plantation and pay them the profits from their portion.

Under this system, villagers formed cooperatives that set up legal “partnerships” with plantation firms. In theory, the system offered them the opportunity to benefit from the technical expertise of the private sector. But it also turned them from farmers who cultivated their own land, to passive, minor partners in large plantations operated by corporations.

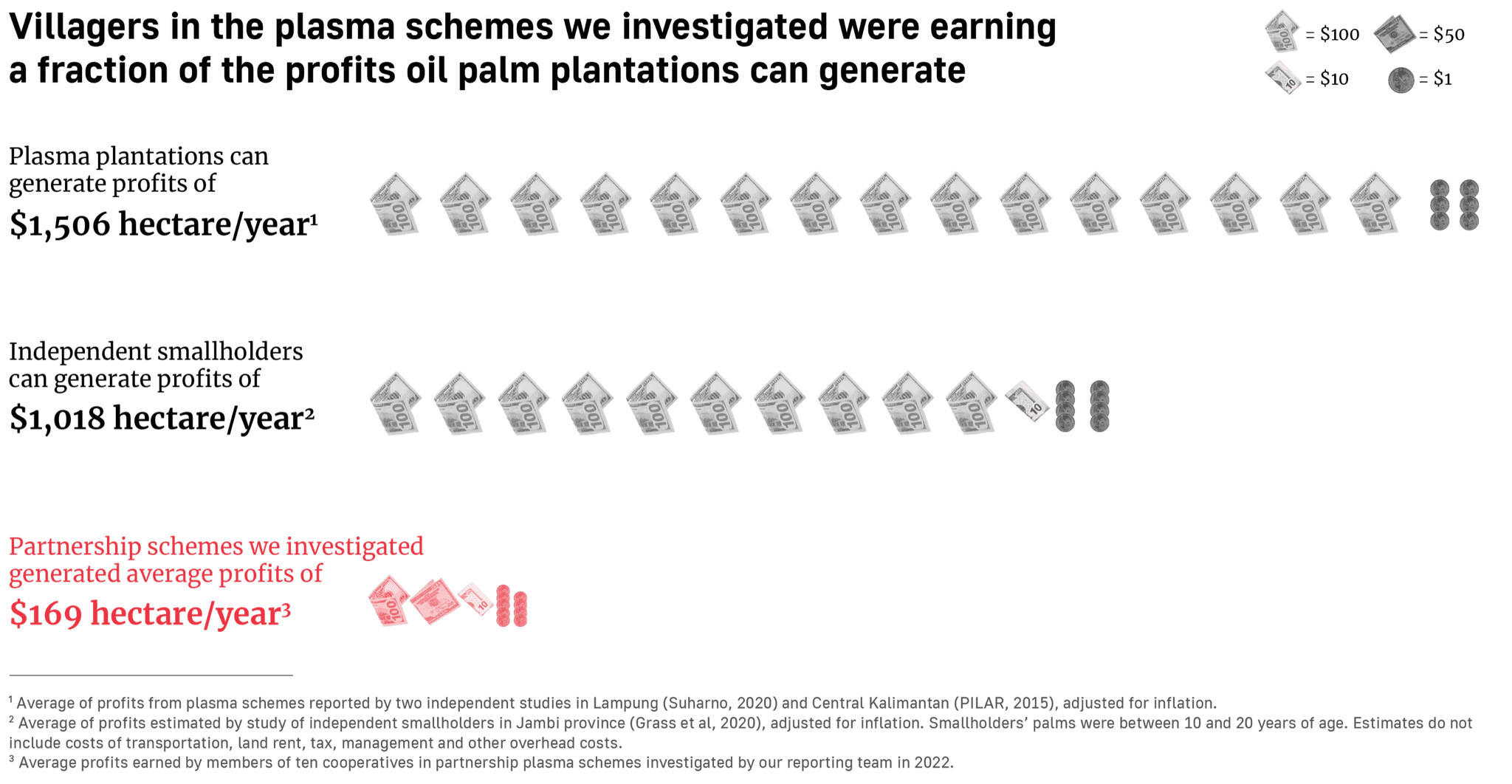

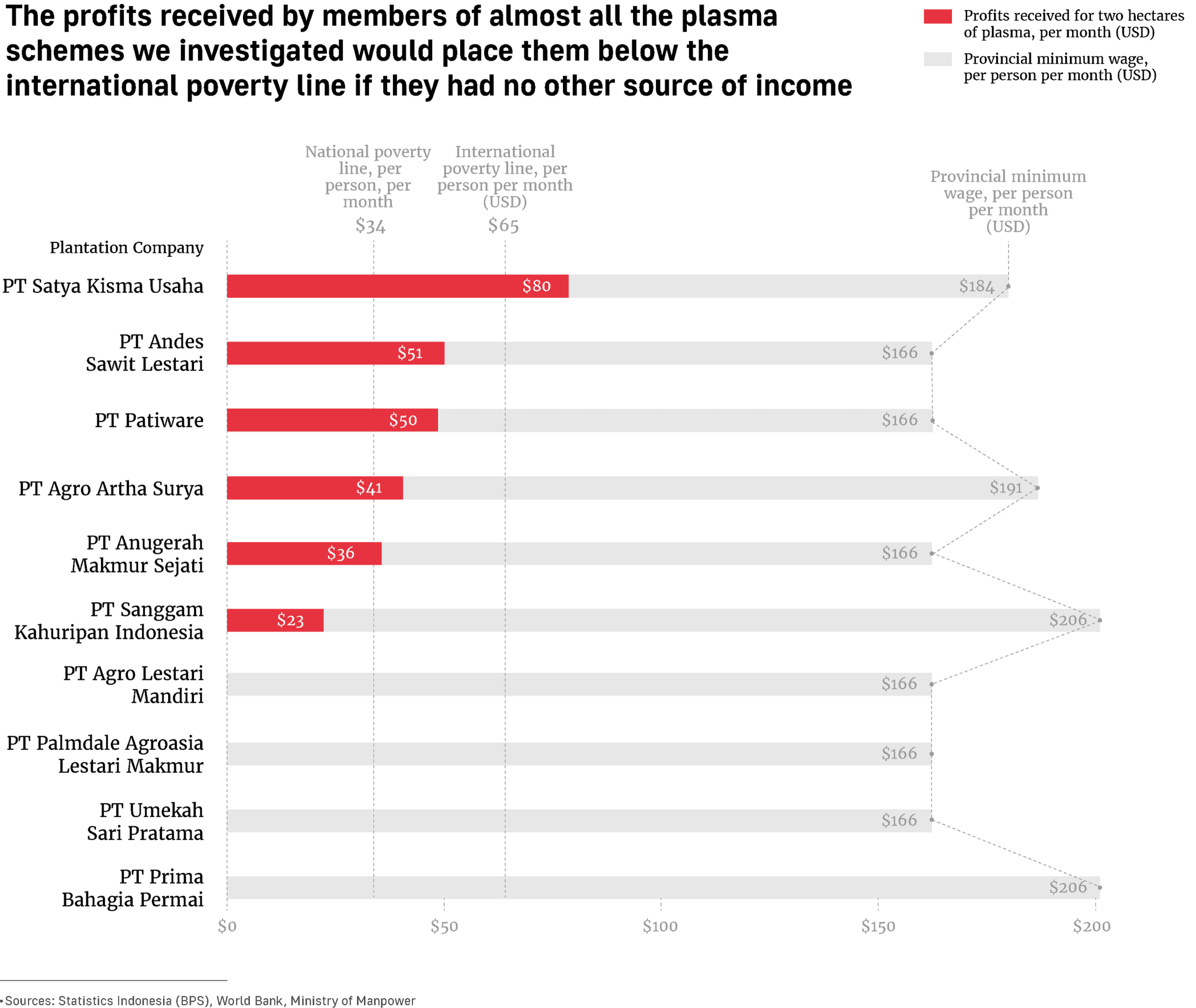

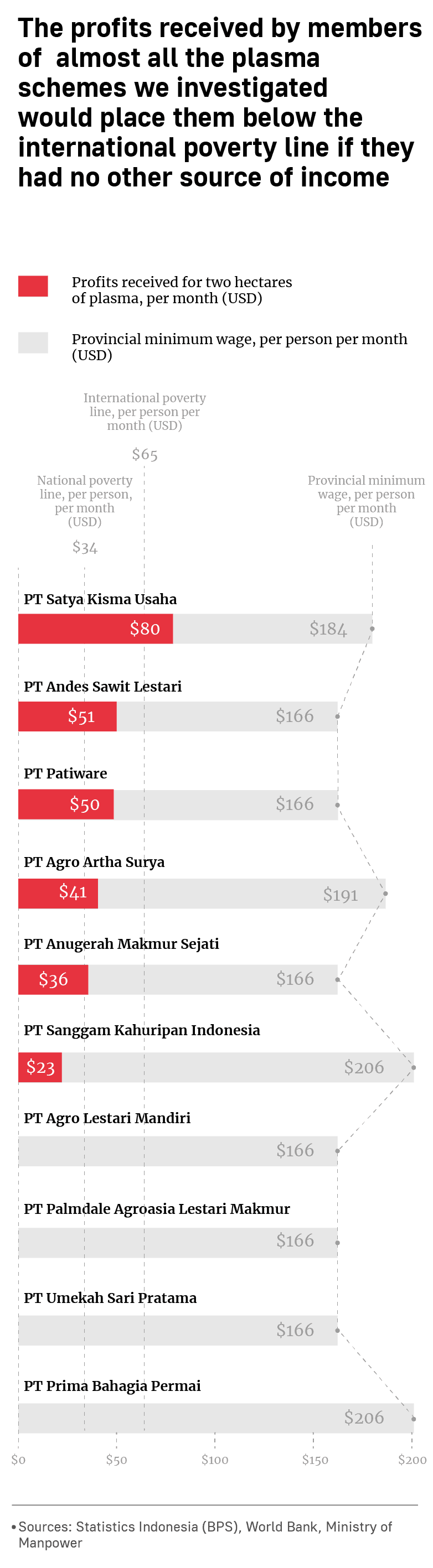

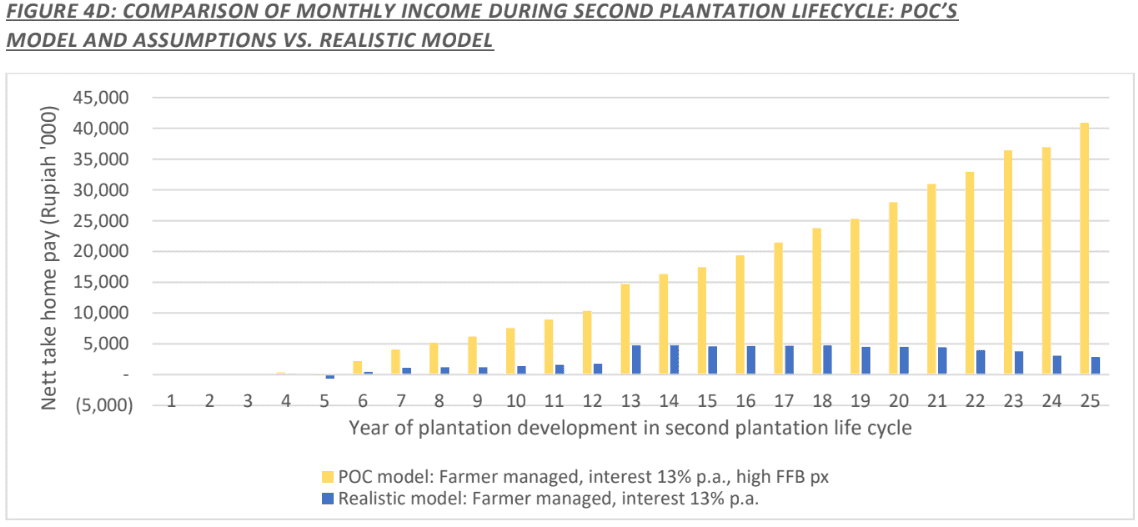

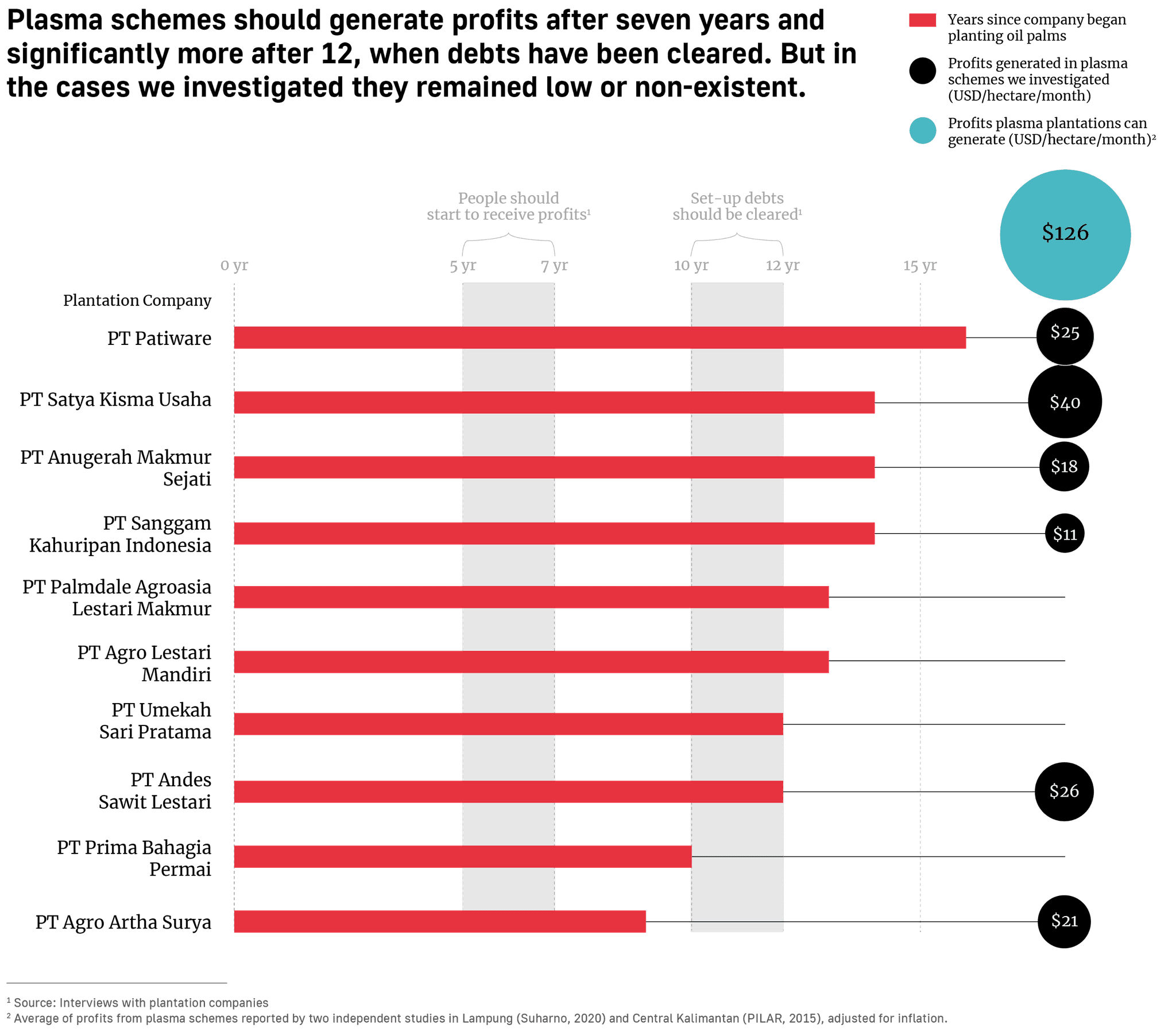

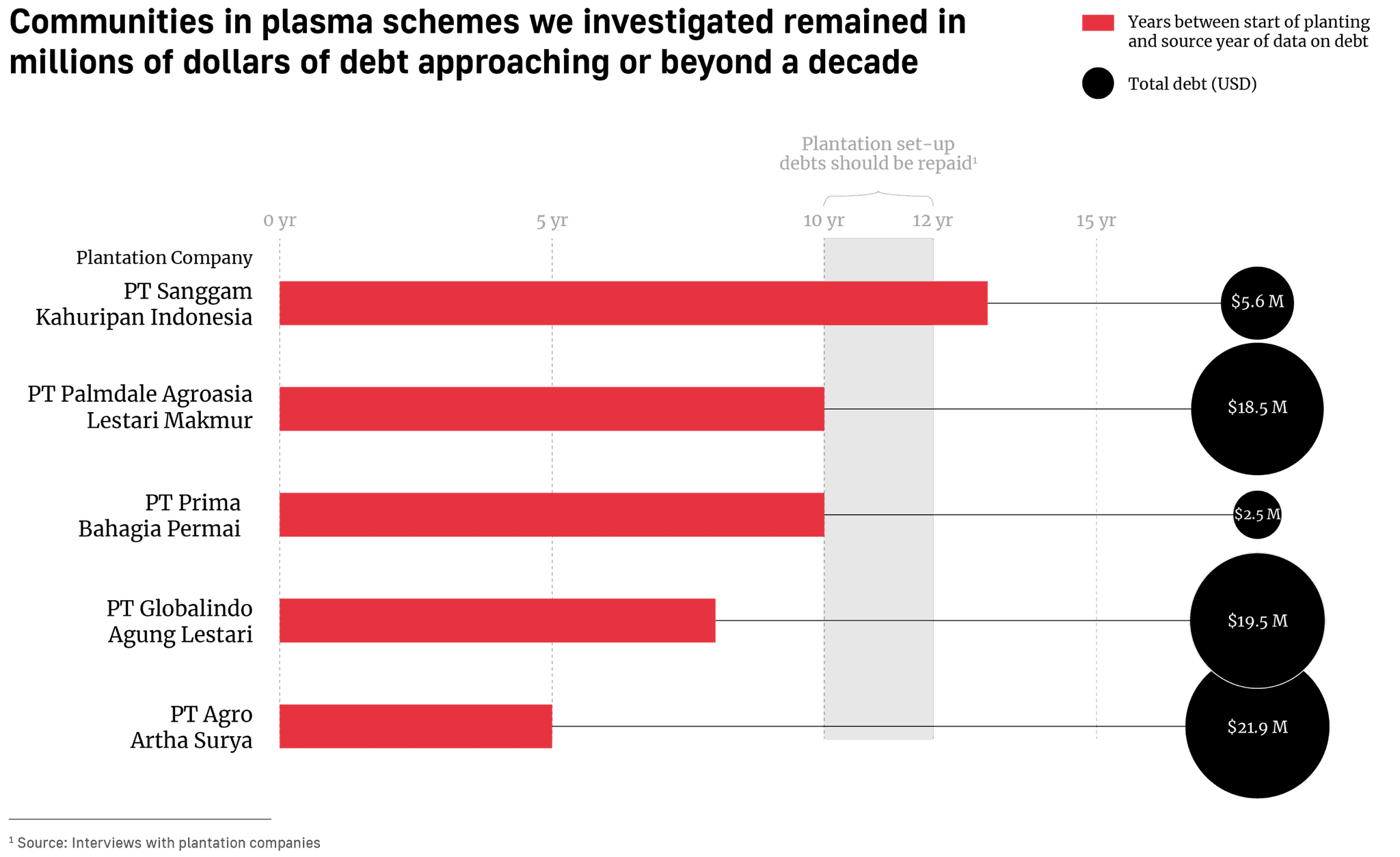

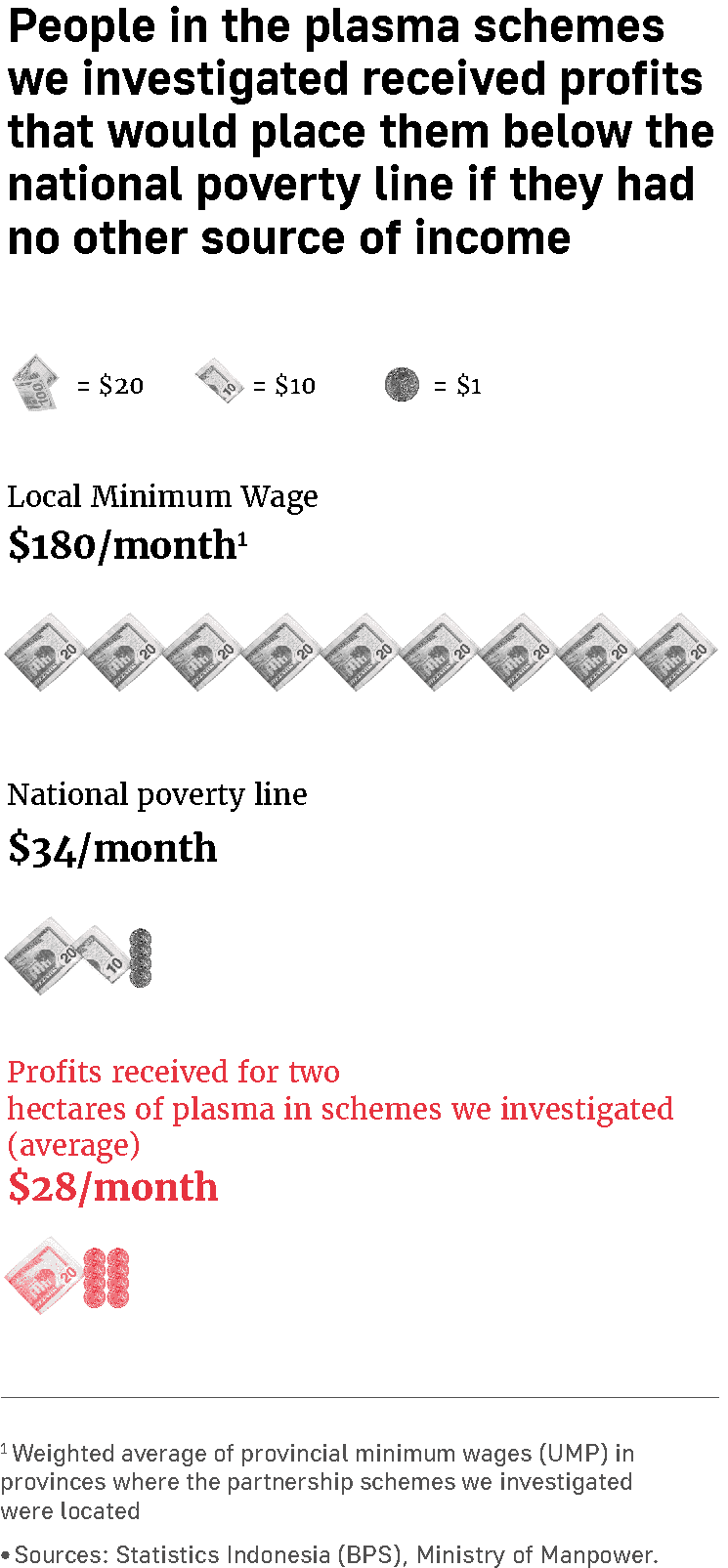

The Gecko Project — together with Mongabay and BBC News — obtained data on the profits received by communities in ten partnerships set up by oil palm firms, collectively involving more than 4,000 people. While plasma plantations can generate profits of more than $1,500 a year for a hectare of land, according to independent studies, in these cases villagers were earning around a tenth of that.

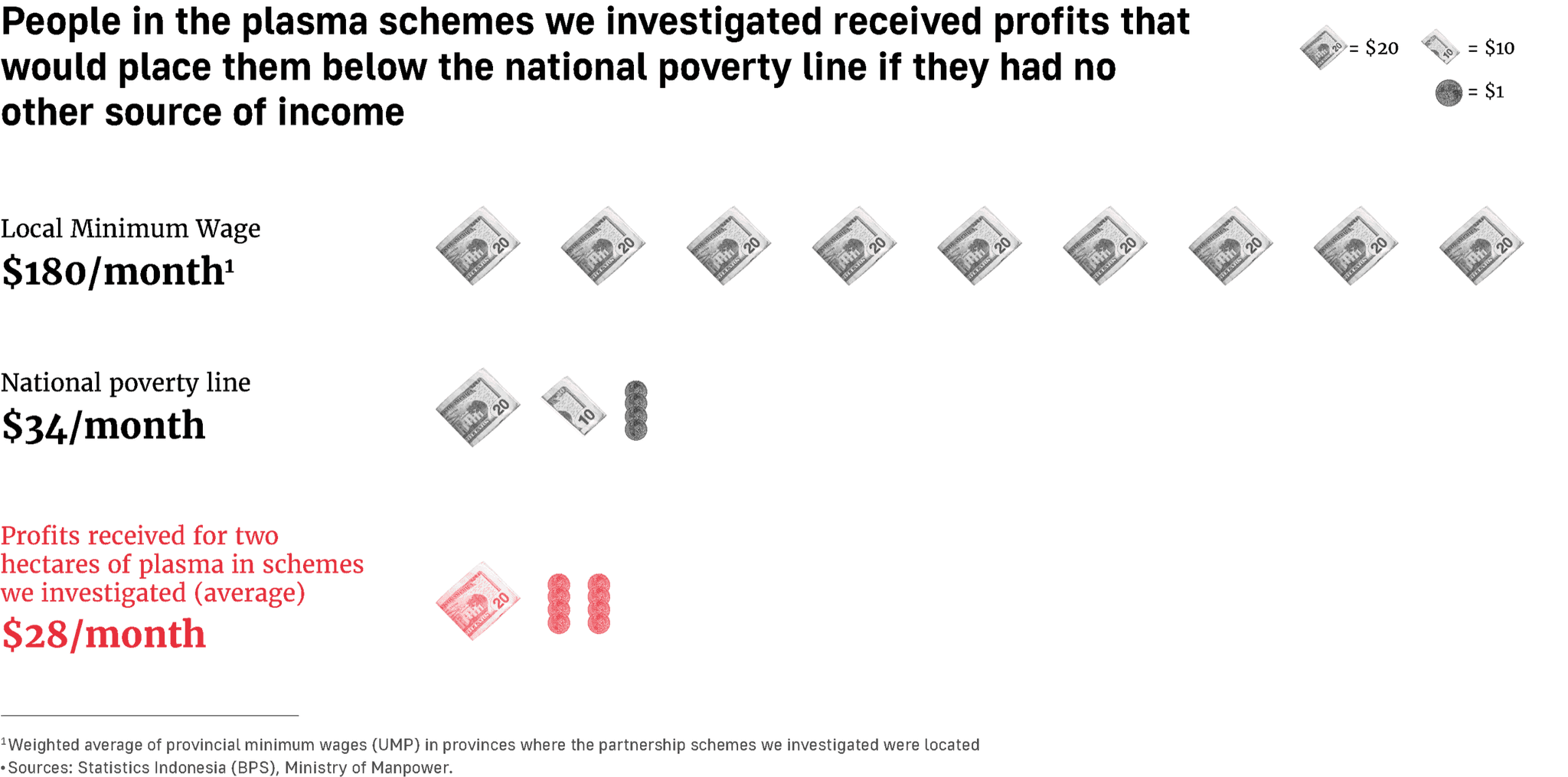

Seduced by the prospect of plantations that could bring economic development to remote villages, they were instead being paid less than a dollar a day, a fraction of the minimum wage and below the international poverty line.

Some were earning nothing at all, years after the plantations should have become profitable.

“What’s surprising is that we didn’t get anything. Not even one rupiah from that company in ten years,” said Martinus, a farmer from West Kalimantan. He had resorted to borrowing money from family members to fund his son’s education, after waiting in vain for the palm oil firm to pay him any profits. “They deceived us,” he said.

Our dive into this model began as part of a broader collaborative investigation examining problems with the Indonesian plasma system. In May we revealed that many companies were failing to provide plasma required by law, depriving communities of potentially hundreds of millions of dollars each year.

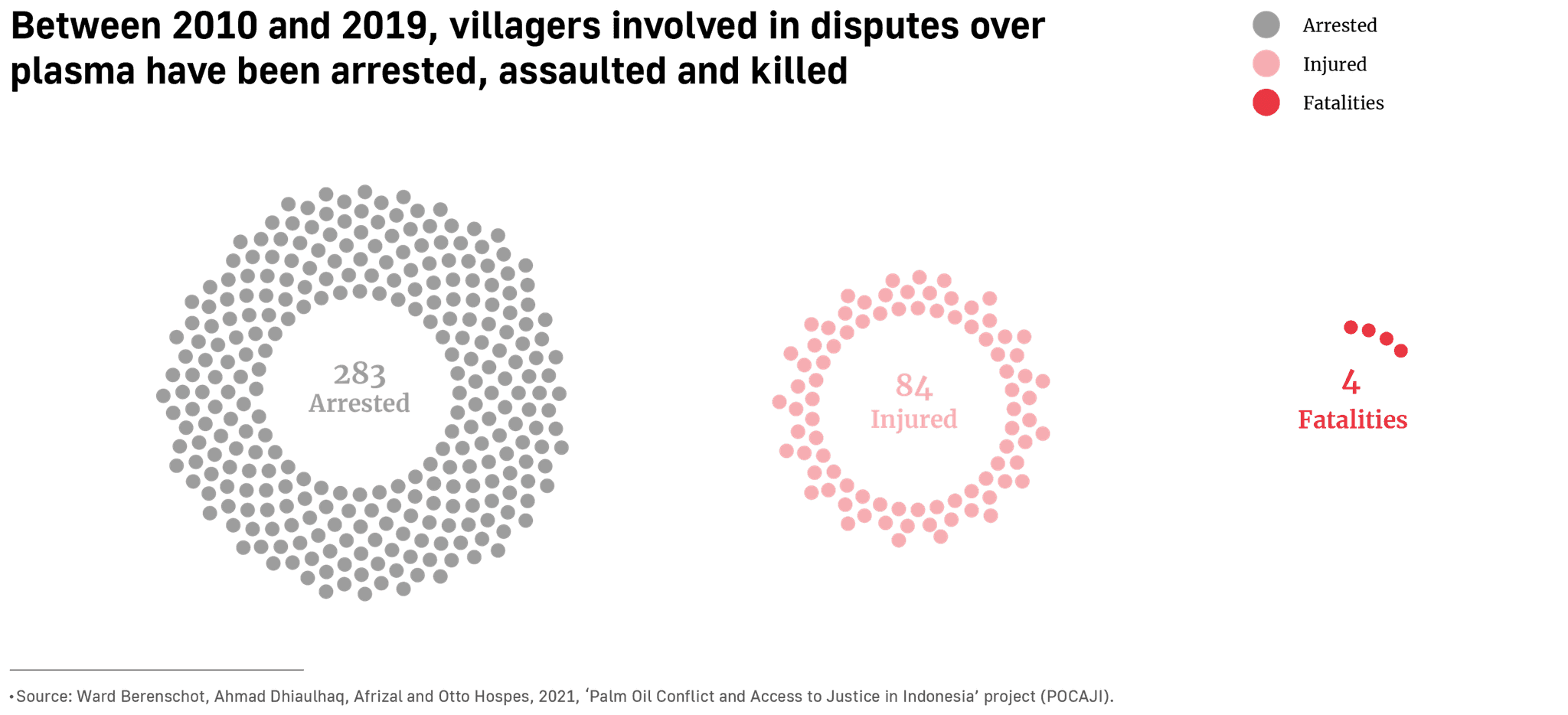

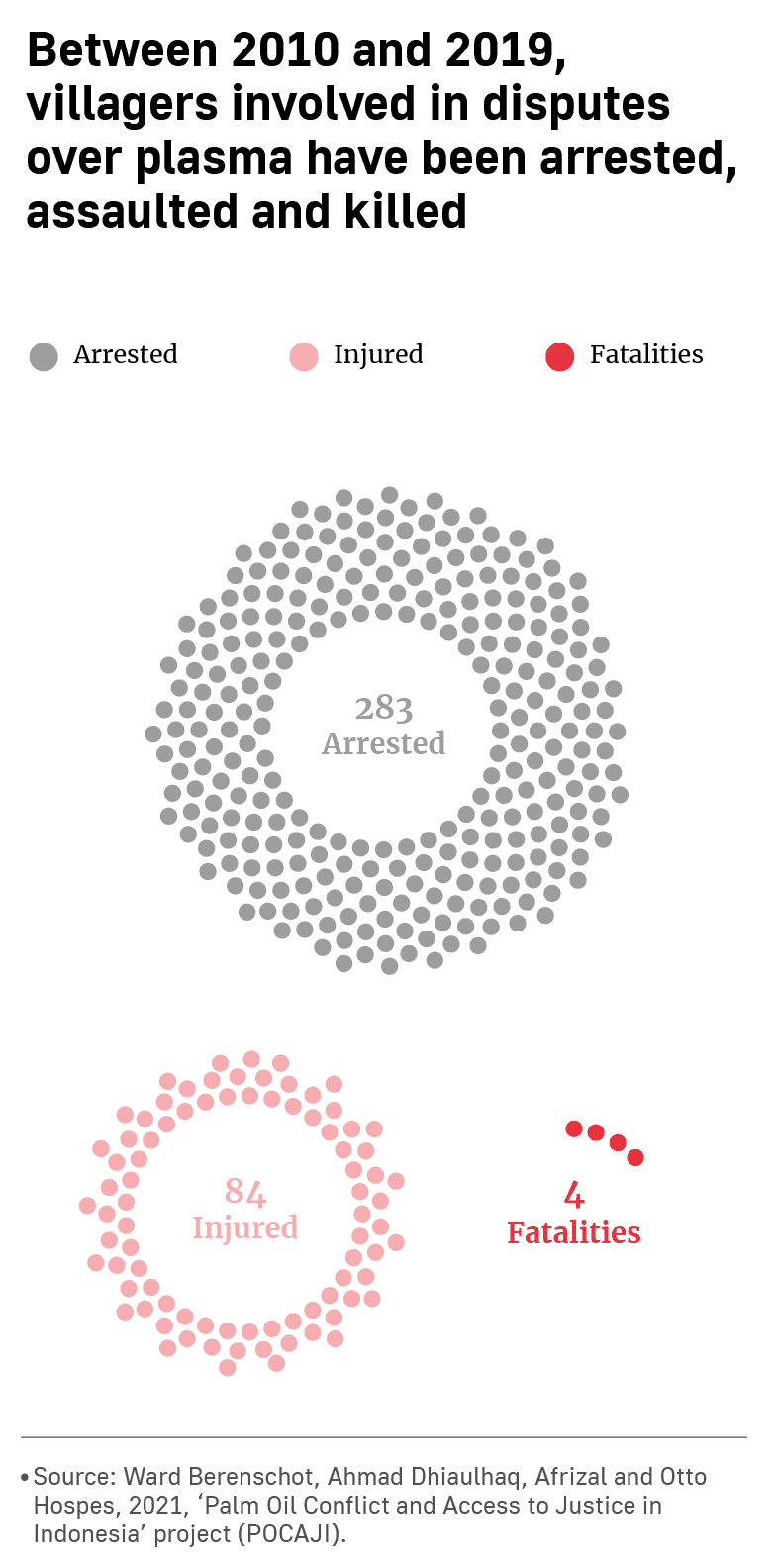

But in the course of the investigation, we also frequently encountered allegations that even where the plasma apparently did exist, communities were earning little or even nothing. Our analysis of reports from the Indonesian media, activist groups and academics turned up more than 70 cases in which such allegations had been levelled in recent years.

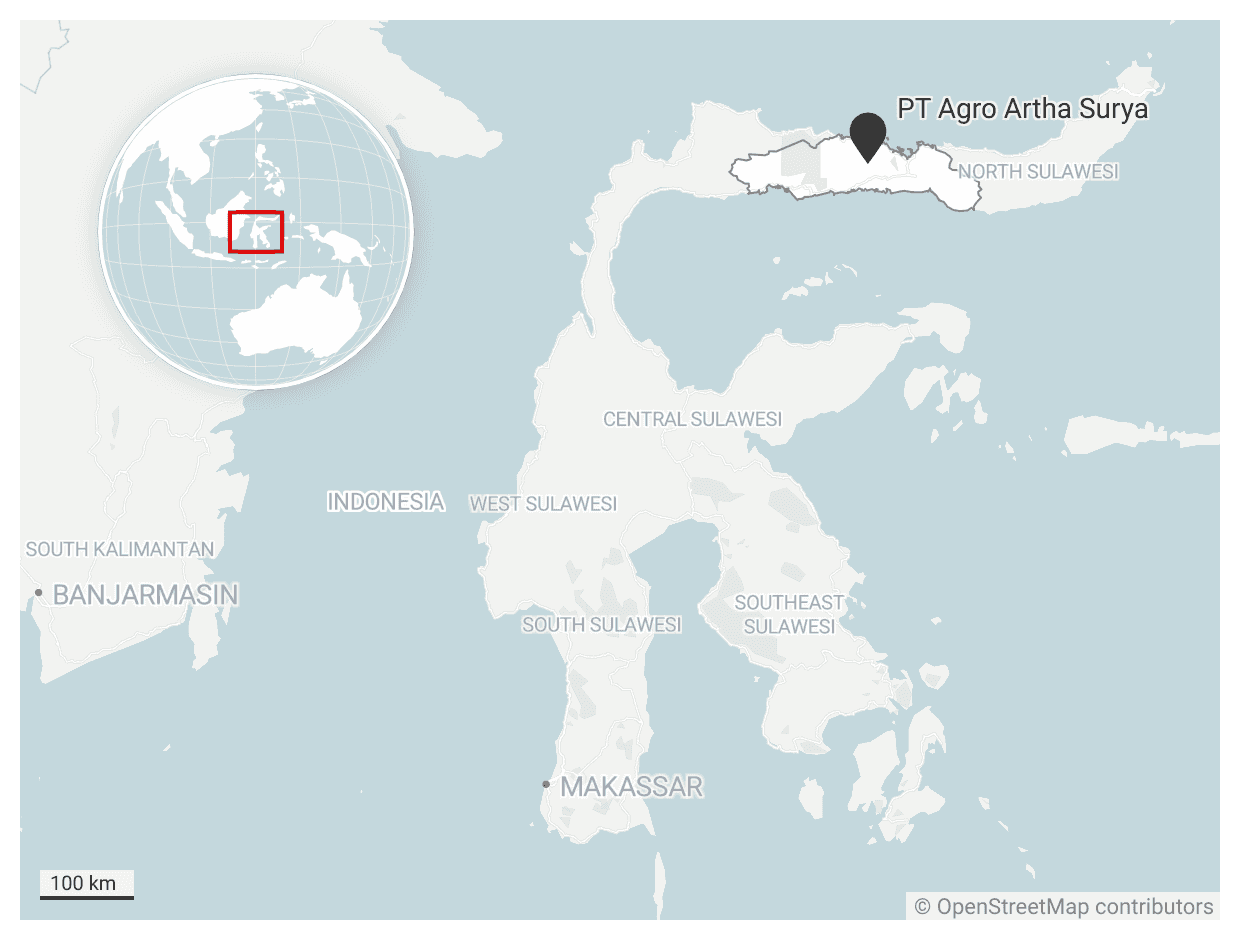

To understand why, we sent reporters to interview communities that had entered into partnerships with 12 palm oil firms, including subsidiaries of two of the world’s biggest agribusinesses. We reviewed court records, contracts, corporate and government data, and interviewed dozens of government officials and experts who have carried out extensive research on agricultural development in the global south.

Our investigation found that communities were signing contracts that gave private companies extensive control over their land and finances for three or more decades. This included giving companies the rights to manage multi-million-dollar loans, used to finance the set-up costs of the plantations.

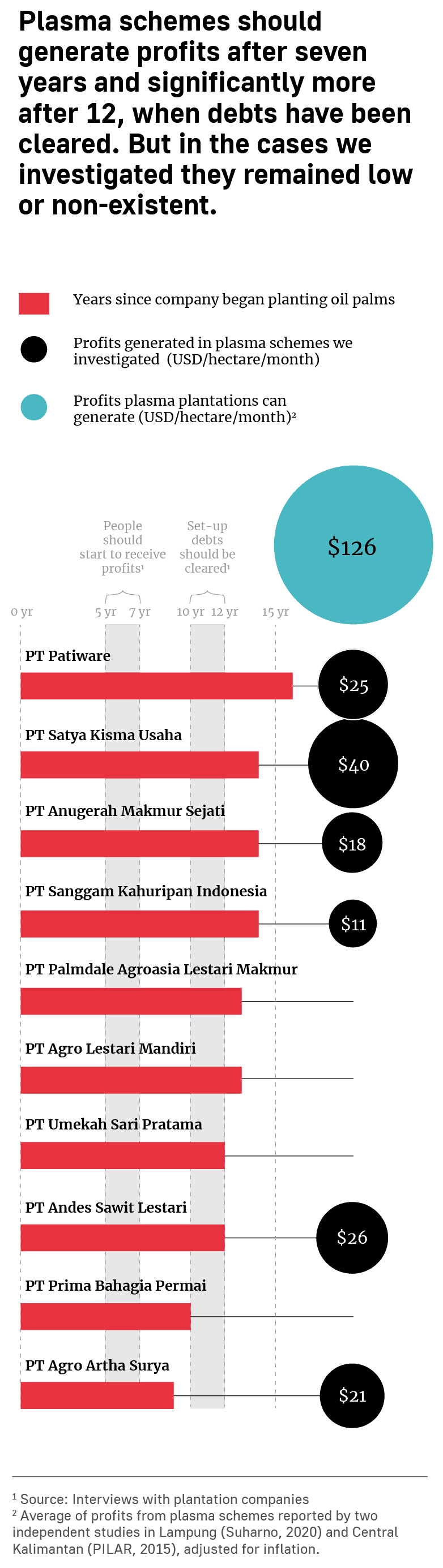

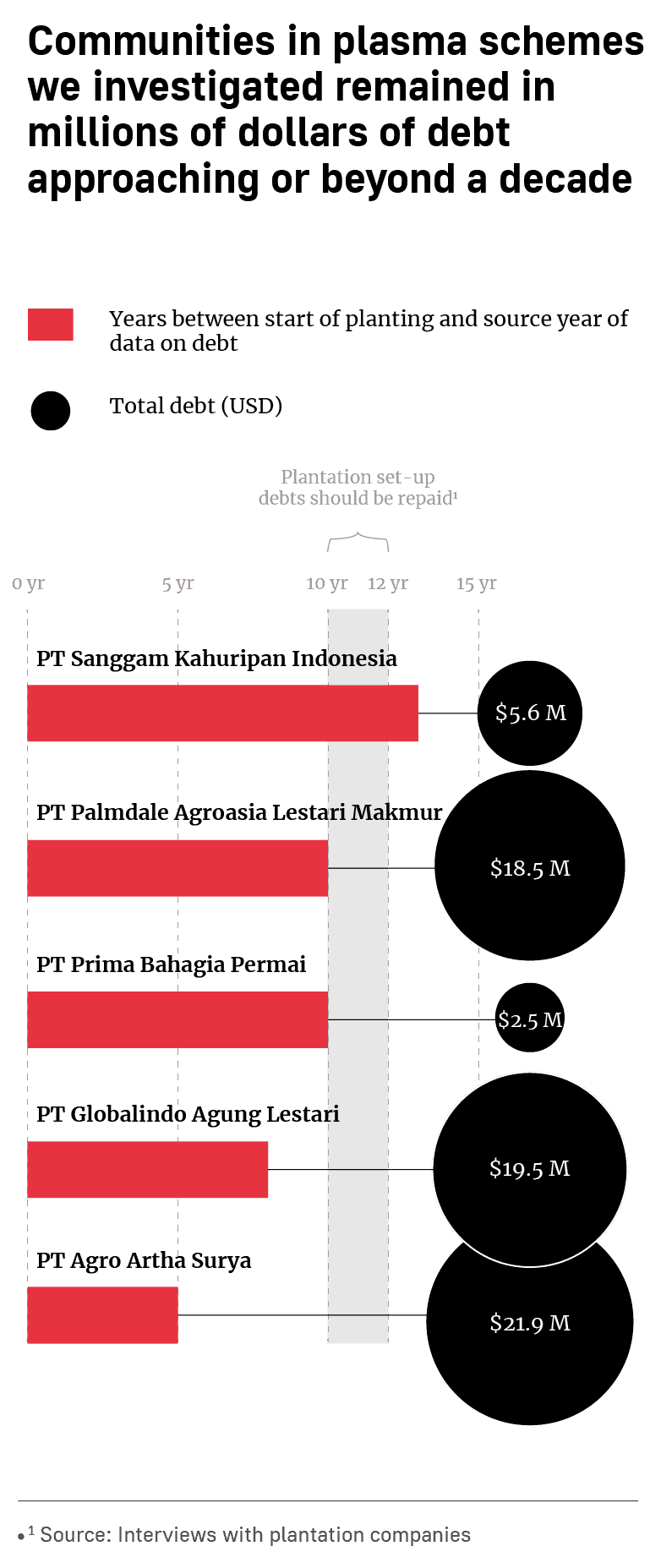

To pay down those debts, and eventually see a profit, the communities were reliant on companies developing and maintaining the plantation properly. But communities we visited had debts ranging from $2.5 million to $18.5 million, a decade after the plantations were established.

With debts accruing interest at an annual rate of 10 percent or more, some villagers questioned whether they would ever pay them off, let alone receive a profit.

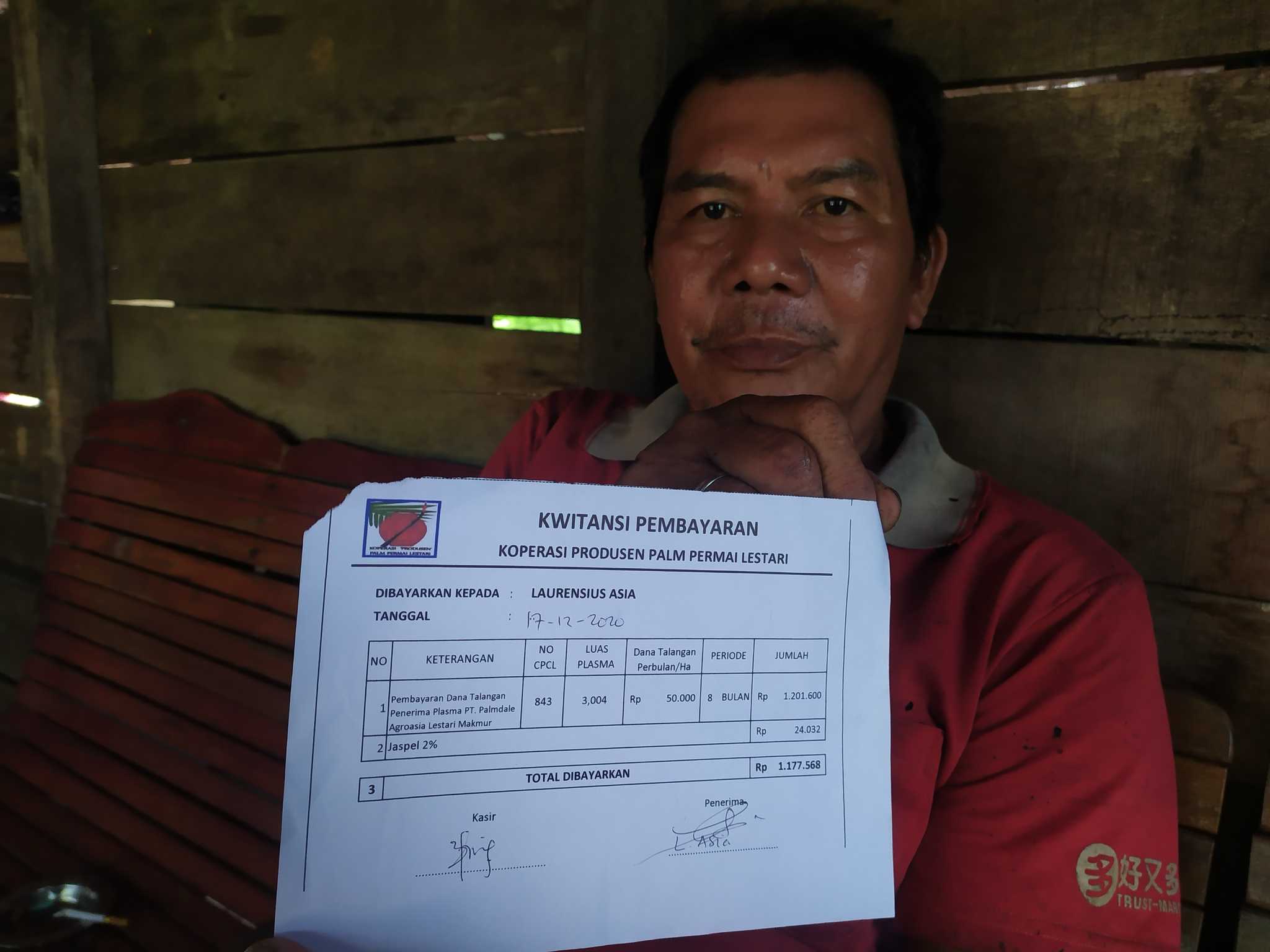

“Before this plantation came, we had never been indebted to anyone for anything,” Siana, a mother of three from Kapuas Hulu, on the island of Borneo, told a researcher studying plasma schemes. “Every time I receive the debt letter from the bank, I think to myself, ‘We are doomed’. Imagine receiving a letter of debt when you never see the money.”

Many of the people we interviewed struggled to determine why they were receiving limited or no profits. In case after case, people who had signed up to partnerships said they were unable to access basic information — from the status of their loans to the location of their portion of the plantation — that would enable them to hold companies to account.

Experts who reviewed five contracts that tied villagers into these partnerships commented that they lacked transparency and stacked the odds against communities. Peter Batt, an agribusiness consultant who has analysed similar contracts for the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, described them as "grossly unfair".

“These contracts are very, very much in the favour of the company," he added.

In response to our questions, the plantation companies we investigated insisted that they operated fairly, transparently and within the law. But our investigation found companies can exploit the opacity in partnership schemes to manage plantations in ways that benefit them at the expense of villagers. We encountered repeated allegations that companies were doing so in the cases we examined.

A damning 2020 report by the Indonesian government’s anti-monopoly agency, known as the KPPU, found that plasma partnerships had created “financial efficiency” for companies, while piling debts onto villagers that suppressed their profits. It found that partnerships made an insignificant contribution to farmers’ incomes because of the “large number of cuts” companies applied to their revenues.

In the past four years the KPPU has investigated at least 20 plasma partnerships on the grounds they may be illegal, violating a 2008 law that prohibits companies from “controlling” smaller parties in partnerships, and is taking on a growing number of cases each year.

But Guntur Saragih, the deputy head of the agency, told us it had half the budget it needed to investigate the situation comprehensively. It is only able to examine a fraction of the partnerships that have proliferated across Indonesia in the past decade and a half, potentially locking hundreds of thousands of families into contracts that will last for a generation.

In the absence of an effective government solution, observers with a close understanding of the problems with the partnership system told us the global companies buying palm oil also need to act. Several major consumer goods firms have committed to supporting Indonesian smallholders, to ensure they are able to benefit from the trade in palm oil. But the companies we investigated have supplied many of the biggest names in global food production, including Kellogg’s, Nestlé and Unilever.

“Large buyer companies of crude palm oil and certified sustainable palm oil have gotten away with too much for too long,” said Piers Gillespie, who spent 16 months studying plasma schemes in Borneo as part of doctoral research. “Because, like it or not, it is absolutely part of their procurement and ESG responsibility to provide more support, training and governance to improve livelihoods and create better outcomes for smallholders.”

“They should be doing a hell of a lot more — and not seek to look the other way or avoid the challenges that the sector’s growth and their demand for the product has created.”

Reporting team

The Gecko Project

Margareth Aritonang, Tom Johnson, Safrin La Batu, Ian Morse, Gilang Parahita, Leoni Susanto, Rio Tuasikal, Tom Walker.

Mongabay

Ari Anggara, Jaka Hendra Baittri, Elviza Diana, Philip Jacobson, Yusie Marie, Aseanty Pahlevi, Yitno Suprapto, Suryadi, Taufik Wijaya.

Independent

Eko Nurcahyono, Sarjan Lahay, Boris Pasaribu, Fatahur Rahman, Petrus Suwito, Masrani Tran.

BBC News

Aghnia Adzkia, Astudestra Ajengrastri, Rebecca Henschke, Muhammad Irham, Haryo Wirawan.

Graphics

Thibi (charts) DataWrapper (maps)

Illustration

Chuan Ming Ong.